THE LONG ROAD HOME by Les Hooper.

It was as inevitable as varnish on a Vogue bird’s toenails and as welcome as a boot up the rear. My life was about to endure a bigger shakeup than balls in a bingo cage. There again, I’m the only one who really cared.

I was flitting through the Daily Herald just after a meagre wartime breakfast of fried bread and bacon in early 1946 when a buff envelope bragging "On His Majesty’s Service" rattled the letterbox and fluttered to the carpet like a shot pigeon. No one had ever written to me before, but I didn’t punch the air with delight. It couldn’t be more alarming if the postman had dropped a hand grenade through the slot. It wasn’t long before I sometimes wished he had.

I tossed the newspaper aside, rescued the letter and stared at it. It glared back and I think it chuckled. I hoped it would self ignite. But it didn’t. I opened it with fingers of jelly. My heart played Auld Lang Syne on my ribs as stark wording explained that good old King George selected me as the saviour of the nation for the duration of the Emergency. Was he hoping for another General Montgomery? Some hope! It didn’t even contain a good luck message. Just as well. My luck had the rarity of a pure diamond in a Woolworth’s ring. The National Service Act giving a set length of service came later in 1948.

‘Duration’ meant until the handcuffs were unlocked or a life sentence and the only emergency I knew of was when a bomb hit the Co-op and we missed our fortnightly eggs ration. Yet the war was over. Germany had gone up in smoke earlier and the Rising Sun sank lower than an adder’s belly six months ago.

Demobilization began on 18 June 1945 and army numbers shrank quicker than a boiled vest. Every soldier was given a release number. It had started at one, logical, for those who survived the war and mine was 74. It might as well have been 1004. The demobs hadn’t even reached number 10 yet. I could soldier on till the next ice age. The future looked as unappetising as samba lessons in the Chamberlayne Road scout hut. I thought of hiding in the cellar. But we didn’t have a cellar.

“Buckle down and get on with it,” crowed my dad, whose face creased like crumpled paper when he grinned. He survived the WWI trenches in France. He always jumped up when the National Anthem burst from the radio and spilled beer down his pants. He kept singing Mademoiselle from Armentieres with a voice like a turkey buzzard with tonsillitis and laughing? Sadly, he believed he was Donald Pearce. He was more like Donald Duck.

Mum remained as quiet as a dozing caterpillar, flopped in her armchair, eyes sad like a nun who’s missed her Ava Maria. Those weepy eyes kept flitting towards a photo on the wall of dad in his army outfit. I don’t know whether it was admiration or regret. Look on the bright side. At least I wouldn’t risk maiming or death down the mines as a Bevin Boy. A medical check decided I was A1. A farce. I had less muscle than a copper stick. Doctors are paid assassins. If they look in an ear and can’t see light through the other side you’re in.

On 21 March 1946, I waved goodbye to Eastleigh and choo-chooed off to Norwich, Norfolk, along with many more local lads and all as happy as mourners at Brookwood Avenue cemetery. One was Sid Gartons whose parents ran a tatty bookshop on Leigh Road. We called him Snotty on account of his name spelled backwards. A thin film of overnight snow covered the ground like dandelion seed, giving the town a fresh look.

Plump Harry Mitchum who somehow dodged the call-up and food rationing was on the platform at Eastleigh Railway Station in his saggy porter’s uniform and wearing a stupid grin bigger than the sack truck he wheeled. He wouldn’t look tidy in a suit of armour. Why did everyone think being press-ganged into the army was funny? The journey was as boring as cake judging at the WI, and as miserable as Robinson Crusoe on Man Friday’s day off.

Monster green army trucks waited for us at Norwich station, khaki-clad grinning monkeys perched in the cabs. The idea crossed my mind that we were the victims of some huge practical joke. Perhaps we were. We were all edgy, like patients in a dentist’s waiting room. I knew how those toffs in the French Revolution felt as they waited for the guillotine head-rolling contest.

We scrambled on the tumbrils and were driven to Britannia Barracks, home of the Royal Norfolk Regiment, The Holy Boys. This was the first time in my life that I had ventured farther north than Winchester. There were no mountains in East Anglia and no snow either. There were groups of fresh-faced boys with rifles marching up and down in the barracks and being shouted at by robots carrying thin canes.

We were shoved into a ragged line by a short corporal with big boots and an unsmiling face like a ruptured warthog. He pushed us through enrolment where ATS girls with deadpan features as interesting as maps of Siberia squatted behind tables and dished out army numbers and identity documents like ration coupons. One girl with a lovely face and an expression as wholesome as a bounced cheque looked at me and said, “Religion.”

I shrugged and answered, “Yes.”

Her blank expression never altered other than a slight tightening of thin lips. “What’s your religion?”

I repeated the shrug. “Don’t know – .”

She snapped, “Church of England – next!” She wrote something on a mysterious form,

I moved on. I should have said Mormon and avoided church parades.

We were suffering a shattering change of life style and those army girls showed as much emotion as mannequins in Marks & Spencer’s. We could’ve been pieces of scrap paper blown in on the wind.

I was given number 14144966, tattooed on my brain. On to another room where White Coats with faces that said they wished they were somewhere else treated our arms like pincushions. Jab – jab –jab! They didn’t make me feel better. My arms ached forever. Large needles bubbling in dishes of steaming water looked like those mum darned socks with.

Next bit of fun was the parade square where the corporal with the miserable face ushered us into squads of 30 spaced out like cabbage rows on an allotment. Snotty Gartons went to a different squad and I never had much contact with him afterwards. From there we marched, well, wandered to our new homes. So far nothing happened to make me want to clasp the army to my bosom or even the other way round. I was jetsam and let my situation drift with the tide.

A wooden hut, our new home, was comfortable if you enjoy bare walls, iron beds, planked floors, naked lights and cold enough for an Eskimo square dance. A gift of ill-fitting denims designed by a mad tailor lay on each bed, and we had to climb into them immediately. No belt, no braces, just a piece of string so your trousers didn’t spend life round your ankles. We weren’t given battledress then. A couple of days passed first to make sure we were going to stay alive before lobbing out full uniform and kit.

A shining stove occupied the centre of the hut on a shallow concrete plinth but it never saw a match. We cleaned it every day, whether it needed it or not. It was polished more often than the king’s Bentley. Anyone who soiled that stove chanced the death of a thousand cuts.

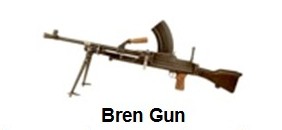

For six week I marched – awkwardly – and walked, ran, limped, wept, laughed, did physical jerks, fired a Lee Enfield rifle with a kick like a mule; dug slit trenches with a spade not much bigger than a mustard spoon, bayonetted dummies wearing Hitler moustaches, tossed Mills bombs – gingerly - and loosed a few mortar shells - quickly. My arms still ached, the rifle badly bruised my shoulder and heavy boots made blisters like balloons. The barrack room looked more like a hospital ward. Had an enemy arrived we would have waved a white flag without lifting a finger.

All this was overseen by a midget squad leader, sadistic Sergeant Murphy from Killarney with features like the Bog of Allen and the charm of a chain-gang guard. He was five-four in height and eight-four in ego. Every night he wobbled on rubber legs to his end room in the hut, often crying like a baby. Perhaps he was singing or mourning a drink he’d left on the bar.

His bar bill must’ve equalled the National Debt. His favourite punishment was making a victim scrape the wooden floor with a razor blade. Some petty crime meant running everywhere for a week. His civilian occupation had been rack operator for the Irish Inquisition. King George paid me three shillings (15p) a day out of his own pocket to frolic in all this pleasure.

This nonsense was called infantry training, which made a sentence of hard labour like a holiday in Hawaii. After five weeks the Personnel Selection Officer, a Captain Shoesmith, who smoked Sweet Caporal cigarettes, had thick rubbery lips, large blue eyes and kept fingering his fair hair, thought I would make a fine military policeman. I thought he wasn’t in love with his job and out of his mind. He occupied a small, grubby office in a barrack hut situated in a remote corner out of harm’s way. An enlarged photo of Ivor Novello hung on the wall opposite his scratched desk. Ivor wore a vague smile as he looked at me. Another lamb to the slaughter.

I asked the captain seriously, “Why would I want to be a military policeman?” I awarded him a pools-winning smile. “The only copper I’ve ever met came knocking on our door and it wasn’t to borrow a cup of sugar.”

His eyes looked like a glass of water. A chewed pencil on his desk explained his beaver incisors. But nothing explained his missing chin. He blew smoke at me, said nothing but carefully unscrewed a bottle of Quink and gently filled a black Parker fountain pen. Instead of squirting ink at me he looked at Ivor Novello for inspiration and with a crooked smile on his fat lips carefully explained why I should be a military policeman, compared with many places he could send me that I wouldn’t like. I decided it would be safer to believe him. So I believed him.

All that body-wrenching infantry tripe did me as much good as a bout of influenza. The PSO didn’t pick me to be a MP because I was tall, determined and showed promise. Mmmm! His expertise was putting square pegs in round holes. Being a MP was a volunteer choice and I allowed him to jump on me and volunteer me as easy as squashing a marshmallow.

He opened a manila folder and shuffled a bunch of papers around to impress me or fool himself. He found a form and wrote something on it. Presumably sentencing me to something nasty. He poked a blobby nose at me over his desk and while rubbing his absent chin with a thumb anxiously pointed out how cushy being a Redcap would be as if his life depended upon it. Perhaps it did. The job would be easier than a bed tester in Dreamland the way he described it in his squeaky voice. Anyway, I agreed because I didn’t want to see him cry.

I was on my way out when he asked my back, “Why did that policeman call?”

I looked over my shoulder. “He was flogging tickets for the policeman’s ball.”

His slanting expression said he didn’t believe me. I expected him to blow me a kiss but he was having a tantrum. He sniffed girlishly, tossed his head and I closed the door behind me. The idea struck me that foppish Captain Shoesmith became very uptight when I questioned his judgement in picking me for a Redcap. Maybe Redcap volunteers were as rare as generous bank managers and I was a soft touch. Maybe his job depended on it. Maybe a hundred things. You never know. It’s a funny old world. I was destined for the unknown by a captain of doubtful gender given the job of filling slots because he wasn’t fit for anything else. I never saw him again.

After being kept in for two weeks we were allowed a few evening hours unshackled. Should we luckily manage to sneak out of barracks we had to return by 10pm or risk jankers or Confined to Barracks, which meant juggling potatoes, cleaning toilets and being chased by power-crazed corporals. We tried chatting up Norwich crumpet but they giggled at our clumsy antics, for we didn’t have the know-how to attract a curious cat. I needed to get out more. Besides which the astute young ladies also knew we didn’t have the bread to buy an ice cream cone.

We were forced to wear uniform all the time. Battledress blouses buttoned up to the neck. Collarless shirts. No ties. On the first day we were given a sheet of brown paper to parcel civilian clothes and send them home. The parcels were like those containing belongings which prisoners are given on release. Life was like prison. Prisoners enjoyed more freedom. We were given three coarse blankets and palliasses. No pillows, no sheets, no pyjamas supplied. Lights out at 10 pm. Curfew. Reveille at 6 am. Bugle playing somewhere. We suffered. Not in silence but we suffered. God knows when this purgatory will end was a universal prayer.

One evening mad Murphy braked to a shaky halt by my bed. The rest of the hut were in the Land of Nod or pretending. My nose was buried in Hank Janson, pretty tame stuff. For a moment I thought I’d crashed a brewery. I stiffened. He usually treated me like a philistine. He belched like unblocking a sink and the acrid smell of swallowed cigarette smoke mingled with stale booze. He sucked his lips and his look stabbed my chest. He wore a sneer that he must have been saving for my benefit. He growled, “Tell me, don’t you make bloody mistakes?” He sounded irritated like an elephant with fleas. He always sounded irritated. He was irritated now because I didn’t irritate him. He didn’t even say, “Begorrah!”

I stood up politely, gave an English shrug and a careless smile drifted across my mouth. Not a happy smile but a smile. I dribbled, “Not when anyone’s looking.” I dodged saying, “Begorrah!”

His thin Eire upper lip curled. “Methinks you’re deeper than the well in our back yard.” He paused and hiccupped. “And no fecking crimes eh?”

I levelled worried eyes at him and pushed the knife in myself. Somebody with a strained voice hissed, “Yes, sergeant. I spat on the stove.”

He sized me up like a lion savouring supper in a zebra herd, eyes were holes in stomach surgery. I could hear blood rushing to his head. “You what…?” His voice gurgled like a Dublin sewer and the comment flew around the room like a trapped sparrow. A bed creaked nearby. His bleeding eyes swept round the room, alighted briefly on the iron idol and switched back to me. His face was a mask of hate. The stove sparkled like polished steel in the bare ceiling light bulb. He almost bowed and didn’t clap me in irons.

I nodded. I didn’t care. I was young. I was shaking like a canary in a hawk’s nest. I was tired of this Irish baboon baiting me. I was a lot of things. Somewhere a hushed voice remarked, “This is stupid.” Aloud I blurted with false courage, “It was a pleasure.” Hank would’ve liked my answer.

Murphy’s drink-veined face turned the colour of vino rosso. By the twisting of his expression he chewed something over in his drink-fuddled mind and it was tough going. The tip of a yellow tongue licked round the corners of his lips. I subsided and withdrew into my shell.

His jaw muscles tightened like a plumber’s wrench then relaxed. The coated tongue vanished and a crooked smile wider than the Irish Sea took over. A spark of life that had been dead a long time clicked in his eyes. I didn’t see it coming and he wacked my side with a fist like a shillelagh. The hate had dissolved. “Ha, ha, that’s savage!” he cried and drifted away on an alcoholic waver like an empty canoe around the Holy Grail to his room, laughing like a hyena with whooping cough. His door cracked shut like a musket shot and silence descended like falling feathers.

I collapsed like a brick on my straw mattress wondering if I needed a surgical corset. I felt like I survived a mincer but lost the battle. He wouldn’t remember anything the next morning. Sid Fellows in the next bed began grunting like a pig under his blankets. The double row of beds with motionless huddled lumps under covers could have been the city mortuary. I dropped Mr. Janson and any strength I had drained away. I dragged a blanket over me like a shroud and joined the dead.

Next thing I shivered as air heavy with early frost shinned steadily through an open window, a mule had kicked me in the ribs and some idiot was murdering a bugle nearby. And he wasn’t playing Danny Boy. Beyond the window a fuzzy dawn began crawling across a steel sky. Miracle. I was still alive. Another day, another pain.

Sad skinny Henry Dingley with the muddled brain and wire-rimmed glasses from the affluent suburb of Tettenhall Wood in Wolverhampton kept wetting his palliasse. They packed him home. He turned to the room, put up two fingers and threw us a mocking grin as he went out the door and back to collecting stamps. The rest of us thought he didn’t have the courage of a dead pigeon. He had a bigger share of it than most. Nor did he possess a muddled brain; he was as clever as Einstein – or as sly as a fox.

The same couldn’t be said for the sergeant, who threatened that anyone playing the same game would be wearing nappies. No one did. We were as weak as kittens. We complained, squabbled, swopped punches, cuddled bruises, stuck together and swore we would shoot the sergeant. We finally gathered our wits and then split almost gaily to go different ways to meet fate in various army units. The biggest kick I got from those six weeks was the happy knowledge that I would never have to go through it again. Adrenalin raced through my veins like a stretch of the white-water Colorado.

The Irish sergeant will rise again like phoenix to torment his next squad. Not that I cared. He was history. I had a peculiar feeling that I never knew him but I still loathed him. I never heard him called Paddy. I thought all Irishmen were nicknamed Paddy. But who cares?

My journey ended in Mychett Camp at Ashvale, near Aldershot, home of the Corps of Military Police, the Redcaps. The hutted camp occupied the same acres as red brick Keogh Barracks, Headquarters of the Medical Corps in which many female nurses were almost as effeminate as the males. I arrived full of expectation like a groom on his wedding night.

I wasn’t surprised, shocked or disappointed. Nor was I jumping for joy. My thoughts were as bright as a parched oasis. The place looked like a Lowry painting minus mill chimneys. It was packed with dummies in sharp creases and white blancoed webbing equipment.

They strode around like beanpoles in impossibly gleaming metal studded boots, which cracked like gunshots on the tarmac with an occasional spark as an iron heel skipped off the surface. This would provoke an angry cry from an important Sharp Crease hiding under a peaked cap: “Pick your bloody feet up!”

The place was shrill with movement like an ants’ nest. Non Commissioned Officers lurked round corners like footpads to ambush unwary recruits. A permanent haze of blanco hovered over the camp like a gas cloud. My mouth was full of blanco. Even braces had to be blancoed when in shirtsleeves and the button straps polished. God Almighty! Blanco dust would glue to my joints the rest of my life.

A host of bossy leaders with whitened stripes, having gone through the mill themselves, wreaked vengeance. They continually shrieked at one another and at groups of trainees in various stages of battling to be Sharp Creases and Shiny Boots.

Tranquility arrived after sunset when the place died and became as quiet as Bournemouth beach in winter. Trainees went to bed with the birds. I drew a short straw in the bed raffle and ended up with a top bunk. I had to hammer in pitons to climb into bed. It didn’t please my vertigo. Still no sheets, no pillows and no pyjamas. The blankets were still as soft as emery paper. The hut had a stove but like Norwich, no coal. The only difference being it wasn’t treated as a holy relic.

On the first morning shaky new boys lined up like lead soldiers on the square for inspection under a blue sky. It was a square where nightingales never sang. After we stood like pokers for ten minutes the Depot Second-in-command strolled round a corner like an actor making an encore. No one applauded. He was a dapper major in the Coldstream Guards with hair curling out from under his braided cap like waving corn. He needed a perm. He came out of a toy box and so short I swallowed an urge to ask him, “How’s Dopey today?”

He tipped back his head and gazed up at me like a street lamp lighter. His neck ached so he lowered his head and with narrowed eyes asked my belly button, “How old are you?“ It sounded as if a silver spoon still stuck in his throat. My belly button answered, “18 and 2 months.”

His head wavered as if struck by a gust of wind and his waxed mustache trembled as his face splintered. “A bit young. We don’t take ‘em under 18 and 6 months,” he said, muttering softly to himself. He may have been heartbroken, but I wasn’t.

I floated up slowly into the fresh morning air. The show was over. Sucker. Thought shadows danced across the major’s port-reddened face as it flowed back together. A band played and my heart picked up the rhythm to Pack Up Your Troubles. Happy? I almost died. His brain somersaulted, he turned to the squad sergeant and popped the dream by saying, “On the other hand he’s a nice tall lad. We’ll keep him.”

I fell back to earth with a mighty crash. I wanted to step forward and stamp on his shiny brown boots but my guardian angel grabbed the back of my jacket. I was a slab of beef on a butcher’s block, a specimen at a slave market. I half expected him to pinch my buttocks.

Being tall changed my life and I became the youngest military policeman in history. It didn’t feel like an honour. Somewhere in the distance a car backfired. A Spitfire droned steadily across the blue sky but it wasn’t searching for Messerschmitts. The Battle of Britain ended six years ago. Mine had just begun. Amen.

I could repeat what I did back at Britannia Barracks. Roll up my sleeves and face whatever calamities I had to face. Easy enough when there’s no choice. I was a prisoner of destiny, as solid as engraving on the back of a watch. I wished I were back home in Eastleigh. I like Eastleigh. Nice people live in Eastleigh. I thought of Eastleigh and white sheets, smooth blankets, Winceyette pyjamas and no one shouting at me. Dreams are just that. Dreams.

My squad leader was Sergeant Smith. He had a narrow face the colour of old leather. A face that had learned more from life than from books. A very pleasant fellow as it happens, especially when seen alongside many other NCOs with heads like pumpkins and who enjoyed crashing their shiny boots on the ground like stomping grapes. They spent evenings dreaming tasks that made the French Foreign Legion look like a Sunday School picnic. I thought of applying for a transfer to a Russian Gulag for respite. I might just as well be in Siberia as far as anyone cared.

Smith’s chest carried a long string of colourful war medal ribbons that he wore with pride. One was the Military Medal, awarded for bravery in the battle for Caen after D-Day. He never mentioned it. He was a breed more rare than a Manx cat with two tails – a military police sergeant with dignity.

To avoid being picked on by Depot warrant officers who prowled around like hungry jaguars, particularly one called Chapman whose nose would hit a wall before he saw it, the sergeant marched us to nearby country lanes for drills.

The Depot RSM was a mysterious, untouchable monster called Percy Sedgewick. He sported a fearsome moustache that bristled like a wild boar’s chin and a shout to drown an erupting volcano. He looked as hard as a coal shovel. Smiles were for politicians kissing babies. Should you be unlucky enough to catch his eye it was like a weasel spotting a rabbit with nowhere to run.

We spent a lot of time in classrooms grappling to learn how the army managed to rumble along and being as bored as a librarian’s cat. All regiments had a Tac. No. CMP was 79, painted on all vehicles. It seemed to me that the army was a bigger miracle than water into wine. Many sluggish hours crawled by learning stuff we’d never need. We were taught everything except Morris Dancing.

Sometimes we were taken to the assault course, which was as exciting as falling off a bus and more dangerous. The place was a mass of ropes, planks, tree bridges, high palings, walls and muddy water. I had no urge to climb Kilimanjaro or jump off Tower Bridge and being Tarzan’s Jane never appealed. I copped out and didn’t stop to pick flowers and avoided all obstacles high enough for eagles to nest.

Cocky young PT instructors with muscles like knotted ropes buzzed around us like wasps in hooped red and blue tops and chastised us and made me run round the course again. I wanted to tell them I wasn’t a flaming chimpanzee. But they knew that.

They led this horse to water but I still skirted obstacles and eventually the wasps would shake their antennas and leave me alone to sting another unfortunate and I would snuggle in the grass and die. They wanted me to run around. Instead I gave them the run around. A petty victory but a victory. They didn’t like it a lot. Once I had a silly thought that life might be easier if I threw my tired body round the damned course. The thought was short-lived. A couple of times we went to a small firing range and fired a few pistol shots. No barn doors were damaged.

Now and then we’d traipse to a Mychett crossroads in white sleeves and learn how to tangle up traffic fighting to escape a jam. You know how it goes. A hundred cars become embroiled in a big mix-up and every Wally behind a wheel blames the other 99. I enjoyed a new feeling of power as I confused drivers. The chaos made fairground bumper cars look orderly. I made more enemies in ten minutes than Dirty Den made in a year.

It wasn’t all down hill. I was waving my arms around like a mad tic-tac man when a black-eyed blonde glared at me from her stalled XK120. She looked good enough to make a cardinal forgo Lent or Mother Superior join the Folies Bergere. Shiny purple eyelids blinked rapidly like a hummingbird’s wings. I tingled. “What are you doing?” she demanded sarcastically in an tinkling voice that would make an owl jump into bed. I reckon she had a rich banker waiting somewhere with his tongue hanging out. I hung, mesmerized, like a hypnotised hoverfly.

“Keep your mind on the job!” came a bellow like a bull from the sergeant on the pavement. I thought I was. The bawling sergeant had a pitted face like a cheese grater and hot eyes trying to shrivel me.

I bravely ignored him, levered my lower jaw back in position like a lock gate and said to the blonde in a voice that sounded like talking under water, “Learning to speak Italian.” I tried hard to stop leering.

Red lips curled into a smile as wide as a Rolls Royce bumper, dark eyes flashed like a Leica shutter. I was glad to be alive. She drooled, “Toodle pip” and crashed her gears as I waved her through.

After two scrapes and seven near misses, the pock-faced sergeant told me that they couldn’t repair cars quick enough if all traffic cops were like me. I no longer cared. I was in love with black eyes.

Whenever we clomped through the village, customers in The Mychett Miners Arms viewed us as invading Nazis and hid under the tables. It’s about time someone told them the war was over.

At infantry training applying dubbin to hobnail boots made them as dull as a black bear’s rump. As I said, at Mychett we had to polish them like mirrors. It was easier to turn lead into gold. The easiest way was to burn off the dubbin first. So many boots went up in flames the Surrey Fire Brigade worked overtime and Cherry Blossom shares hit the ceiling.

Eight weeks of that was followed by two weeks motorcycle training. That was straightforward. Life almost became normal. We learnt to ride and fall off motorbikes. One exercise meant riding over bumps standing on the saddle like a circus act. Why? Who knows? After training I never once had reason to ride standing on the saddle.

We roared up ragged grassy hills and throttled gently down rutted slopes. We splashed through mud and water and skidded through sand and gravel. Again I don’t know why. Charlie Cairoli could learn to ride a motorbike in an hour without churning up the countryside. Shelling peas is more dangerous, although sometimes the bike rebelled and tossed me aside like a rag doll. We were just kids at a noisy playground. A couple of recruits were back-squadded to complete the course again. This was so the instructors could pretend learning to ride was difficult.

After ten weeks someone down the pub or equally remote decided that we had reached the pinnacle. It felt like ten years. A brand new stripe decorated my sleeve. A tick of success. I’d wriggled through the course on my belly like a grass snake. Was it tough? Well, it wasn’t jolly hockey sticks. No frills. The final gift from the Depot was a suspicious mind. An essential cop accessory but like all sports takes practice. I’d really cracked nothing.

Ignore the motorbike games and I could have worn a red cap cover the day I departed Norwich and been just as wise. Well, nearly. The thought weighed on my mind like an anchor. Other than causing confusion among traffic what had I learned about being a military policeman? All I went through served as much purpose as building an igloo in the Gobi Desert.

To hell with it. I couldn’t be happier if the Archbishop had invited me to tea with the Angel Gabriel. Good God, I’d beaten the system! We lined up on the parade ground like a palace guard for the final bawling out. Sergeant Smith shuffled among us flicking invisible specks from our uniforms with a clothes brush like an owner fussing over a Chihuahua at Crufts. Spruced up like a tailor’s dummy, I tried not to move in case I bent a crease. My own face leered up at me from my toecaps.

We then stamped merrily around in our neatly laced extra shiny boots with polished studs and lace holes and the blanco cloud caused nearby Aldershot to switch on streetlights. This was called a Passing-out Parade, which means you’re well and truly hooked with suicide being the only escape. It happened my squad was voted best of the bunch, which proved that gentle handling works greater wonders than Double Diamond beer. Sergeant Smith deserved a knighthood in addition to his MM. I liked the weight of my stripe. At last I felt that it wasn’t only my mum who wanted me. Poverty remained though on 15p a day.

The next time we all lined up was to decide our next move. Black clouds overhead. Out of the 200 or so jumpy men waiting nervously like a sixth form for exam results, 100 were detailed off to go overseas. This group included me. Had I stood at the other end of the parade where the sun broke through I would have stayed at home. At the time my heart raced like a drum roll at the thought of foreign travel. We weren’t told where we were headed. We weren’t human; just numbers.

I never hit Mychett again but that doesn’t mean it never played an important part in my life. I wouldn’t miss it but I’d never forget it, just like gastroenteritis. As my thankful feet carried me past the guardroom for the last time I knew how Papillon felt when he departed Devil’s Island.

Anyway, in due course off I travelled like a Skegness happy holidaymaker to hutted 48th Infantry Division, located on the outskirts of Horsham, in lazy Sussex. This was where the army herded military policemen before dispatching them overseas. Our lives there were overshadowed by RSM Baron, a short, lumpy man full of self importance like an overweight coal sack and a mouth bigger than the Blue John Cavern. If he suffered from leprosy we couldn’t do more to avoid him. The dump didn’t own a barrack square so tubby Baron got his kicks by chasing us like a dog after rabbits wearing out the tarmac road which ran through the camp.

Some liked to spend a lot of time in the Church Army canteen, run by a lovely lady called Joan who wore cropped blonde hair and a smile from Hollywood and sometimes slipped me a free iced bun. A middle-aged Hollywood. A mug of sweet tea and bar of Kit Kat was a calm oasis on a stormy island.

We still had no idea what those distant mandarins had decided what to do with us. But the military police obsession with motorbikes like a drug addict never wilted. We were each allocated a machine and went out for a trip round the south coast countryside nearly every day under the auspices of an instructor. With a couple of others I got lost, thereby going on a joy ride wherever took my fancy and had a whale of a time without NCOs breathing down my neck. The famous seaside towns of Brighton and Eastbourne were good places to visit. They were packed with happy post-war holidaymakers that summer and it was like a day at the fair to forget the army and join them for an hour or two.

Of course, we were threatened with life imprisonment if caught but it was difficult to prove that we became lost deliberately and I, for one, never received any punishment. I got away with much because I looked young and innocent. I was young and innocent. Keep your nose clean, don’t get caught and army life is tolerable. I was a quick learner.

This unit had a visiting lady doctor. I didn’t know that such creatures existed outside schools. She wore gray tweeds and gray shoes with flat heels. She stood out like a donkey in an elephant herd. No way would I strip and be prodded about like a newborn baby by a gray scraggy middle-aged piece of skirt I didn’t know from Betty Grable. Even to music. The number of soldiers reporting sick dropped quicker than the odds on a Derby favourite. She prevented more sickness in a week by her mere presence than St Bartholomews managed in a year. I bet she’s got cold hands. But I couldn’t duck the final twitch of her stethoscope making sure I was fit to die abroad.

She parked her bike behind the surgery. She looked like a Boots body chart. Her room smelled like Boots. She smelled like Boots. On the door a piece of white cardboard stuck up with drawing pins said H.D. WALLACE-THOMPSON MD. Had to be Henrietta. Horn-rimmed glasses hung round her neck by a tatty piece of string. She never wore them.

Her stethoscope was as warm as a husky’s nose stuck in a snowdrift. Her gray eyes ran over me like exploring spiders and I stared past her gray head at a fly on an eye chart pinned to a gray wall. It crawled over the G. It would. The heat rose in my cheeks hot enough to start a bush fire. She smiled, bedside, which was as genuine as a twelve pound note. She had teeth, not gray, but dentures as gleaming white as piano keys.

After surveying me like a cartographer with a new map she muttered in a gray voice, “Now then,” and her teeth clicked, “have you any problems?” I was about to supply a list before realising it was doctor talk.

“Would it make a difference?” I politely inquired.

The bedside manner turned a little chilly. Then a trace of humour laced her voice. “I see,” she clicked sarcastically, “you’ll do.” Goodness, she was human after all. For a split second she almost dropped that superior veneer adopted by doctors. I didn’t see but hoisted up my pants and strolled out no fitter than when I entered and none the wiser. The next reluctant victim brushed past me on the way in. And all the time those gray eyes stuck to me like mud on a blanket. It wasn’t curiosity. Doctors have heard everything even before they take the oath. Everything.

Those spinster tweeds! They probably doubled as pyjamas. She had more concern for a wrinkle in her gray stockings than me. Now I’m not so sure. The stethoscope was only a prop. Even so, I was just another squaddie who didn’t die on her so got the passed fit signal.

At last we learnt our destination from a simple badly typed sheet on the notice board. A vague place called the Middle East. Some joker said Arabs live there and take your bucket and spade. We weren’t told exactly where. We decided it meant Egypt, which was a pretty good guess although not strictly on the nail. There were a lot of countries in the Middle East. Still are, I believe. We were destined to travel on a route called Mediterranean Lines Of Communication (MEDLOC).

Eventually we were conveyed to Horsham train station and travelled to Dover, the port shell-scarred by Germans from across the channel and whose white cliffs Vera Lynn sung about. I didn’t spot any bluebirds.

We were packed in Dover Castle overnight, the stone shack where Henry II went for his ozone shots. We had iron beds in a long gallery with leaded windows with just a single blanket supplied for our journey. Few slept in the freezing cold and we didn’t undress. Penguins might have enjoyed it. I don’t know how King Henry coped. Perhaps he had more than one blanket. I felt safe in the icy castle although no archers manned the battlements.

I woke up in the middle of the night and above the communal snoring of fellow slumberers heard drumming by the ghost of a 15-year-old headless drummer boy, decapitated by robbers. On the other hand it may have been Curtis’s false teeth rattling in his skull. Eventually the drummer boy got sick of drumming and I nodded off. Or Curtis took his loose teeth out.

Sergeant Curtis, a large uncouth character built like a Sherman tank, was in charge of the draft. His face looked like a stale suet pudding and his size showed all the weaknesses of a solid brick wall. Nothing worried him, unless he had a wife. I don’t think anyone ever threw him out of a window. He looked as if he would bounce you for a shilling. When hatless his scalp shone like a beacon in the light and a fly landing on it needed skid chains. He quickly decided we were a bunch of useless kids. He was right. His voice sounded like shovelling gravel. But he wasn’t a bully, merely a moron. He had all the charm of an undertaker’s worn socks.

One time Terry Barraclough said to me, “Curtis’s trouble is he thinks he’s tough.”

I gave him a long thoughtful look and replied, “I think he’s sure of it.”

Next in line stood Corporal Tulloch, cool as a polar bear’s rectum and as spivved as a Brylcreem ad. Everybody liked him and he never used the heavy hand. His only blemish was a parrot face but we tossed him seed and forgave him for that.

I was unfolding my blanket when Corporal Tulloch came up and said, “I ought to warn you that Sergeant Curtis thinks your attitude leaves a lot to be desired.”

I shrugged and said, “I never hardly speak to him. Anyway, even he desired the rest I’m not selling it.”

Tulloch laughed. “I might tell him that.”

I laughed too. I don’t know why.

Nothing changed except whenever I was near Curtis he looked at me with a strange light in his eyes. I did wonder what he had against me. I decided it must be my good looks.

Early next morning we staggered into life as spritely as breakfast call in a care home. A harsh sun tried to melt an inch of frost, which lay like an Arctic snowfield. The brightness felt like a hot daggers in my eyeballs. Down in the harbour an icebreaker’s hooter sounded reveille. We buckled on our bulging packs, hoisted ten-ton kitbags on to bowed shoulders, crunched to the docks and scrambled up a swaying gangplank to board a cross-channel ferry. Climbing the Matterhorn would be easier.

The day was still rubbing sleep from weary eyes and I was tired already. I’d sailed on a ferry before – a small Red Funnel paddle steamer that churned the water like soapsuds between Southampton and the Isle of Wight. This one was not quite as big as the Queen Mary.

The Channel was as smooth as an ice cream sorbet, which fooled me into thinking I’d make a good sailor. I waved goodbye to England. England didn’t wave back. As we departed the harbour a black painted trawler crept in towing a flock of gulls looking as if they were on strings. The ferry cut through the glassy water like slicing sponge cake and ate up the 25 or so miles to France like a hungry whale in under two hours.

At Calais the ferry leaked its passengers into a whirlpool of khaki. The port looked as if a bomb had hit it. It had. Many bombs. The prow of a half sunken trawler stuck out of the harbour like an inquisitive seal. There were wrecked pillboxes and houses with open rafters and walls pitted with bullet holes. Confused soldiers swarmed around the quayside area like crazy bees. Chaos reigned. Enterprising French locals oozed in and out the throng, among them small boys on the scrounge for chocolate and cigarettes. Begging’s the same in all languages.

Some of the boys bartered for chocolate with gestures that would shock a drunken sailor in a bordello. A couple of scruffy Frenchmen in dark berets produced dirty sepia postcards like magicians in exchange for fags. They weren’t pictures of missing relations they were searching for. My young eyes widened like opening sunflowers. I’d never seen anything like them before.

Somebody somewhere gave an order. Movement staff soon dived into the fray, cajoled and bawled and some sort of order returned. Our draft was driven on to a nearby train like a herd of sheep, eight to a compartment, packed like a rack of lamb in a butcher’s window. The train was older than Notre Dame. The smell of grime and garlic hung in the air so thick you could cut out lumps and screw them to the wall. All the windows were smashed. We sat and shivered like strippers in an igloo for a couple of hours before darkness drifted in and with a large burst of black smoke the train pulled away grunting like a buffalo with corns.

The journey took us overnight from Calais to the south of France –Toulon naval base. It was as enjoyable as having a tooth out and as tedious as a dripping tap. A fierce wind whistled through the broken windows like a banshee and huddled under one blanket like an Apache in winter we slept fitfully upright and freezing as the chugging train cut through the cold night. Firebox grits flew in and searched for our eyes. There were a couple of food stops where everyone stretched cramped legs and were served tinned meat and veg in buildings like aircraft hangers. I can’t remember where. We halted at the Gare de Lyon in Paris in the black and it might just as well been the down line at Scunthorpe railway station.

What I do remember is that there was beautiful, tasty white bread available. Back home we were told occupying Germans kicked the French around from eyebrows to breakfast time. It didn’t seem starving was included. We hadn’t seen white bread since 1939.

Daylight gave birth struggling to forget the night shadows. Some of the roads eyed from the train as a misty day settled down were lined with burnt out army vehicles looking like a straggling breakers yard. They must have been strafed from the air. At one stop a couple of miserable shaven–headed women ducked away from the rows of eyes watching from the train. German collaborators punished by the Maquisards. Their faces were dry biscuits and would crumble if touched and wore blank expressions as if nothing could hurt them any more.

We didn’t stay in Toulon. We were stashed in a transit camp near the city, a place called Hyeres. We were there for over a week. Opposite the main gate was a brick two-storey house where every night soldiers lined up to sell items of kit to the house owner. I couldn’t fathom how all this crime was being committed in the open without anyone being nabbed. The sums received were paltry and feathered no nests. I wondered what would happen to us next.

After a couple of weeks languishing in Hyeres we were transported to Toulon docks. The harbour was littered with the scuttled wrecks of French battleships looking like stargazy pie, nuzzled by boats still floating. There we embarked on the luxury cruise liner, the RMS Durban Castle, a Union Castle ship appropriated for a troopship. We didn’t see luxury. The conditions were precisely the same as the primitive existence of Nelson’s sailors without spittoons. We were divided into mess decks of around a dozen men. We sat at a long table and one man would be detailed each day to fetch meals from the galley somewhere in the belly of the ship. The food was dredged from the ocean floor. Small eggs had green yokes. Somebody said they were Egyptian. It was 30 years before I even looked at a hard-boiled egg again. My food intake would leave a mouse starving.

We were each given a piece of canvas with rope ends, apparently called a hammock, which was slung above the table each evening and slept in. I would’ve been more comfortable in a bed of nettles. God knew I was no sailor and sent high winds and steep seas to prove the point. The rocking ship turned my stomach inside out all the way to Port Said. The ship smelt like a split sick bag. Yellow men crawled into the scuppers to curl up and wait for the painless relief of death. Healthy ozone wasn’t having much luck against the smell of stale vomit. I would never believe a Sunny Med ad again. One day I dallied with beef stew that tasted like a tramp’s back pocket. It ended life being washed ashore in Cyprus. The only times the rising and dipping stopped for breath were stops at Tripoli and badly bombed Malta.

We disembarked at Port Said, Egypt. My clearest memory of the port is a huge Johnny Walker whisky advertisement marching along the quay. We boarded a train for Cairo. The compartments had wooden seats and no windows. We stopped a couple of times. At one station a man had his watch snatched from his wrist. We soon learnt that thieves abounded in Egypt. Most Arabs wore towels on their heads and long drooping gowns that never saw laundries.

We ended up in the Military Police Depot at Almaza, near Cairo airport at Heliopolis. We lived in tents on the sand. Could’ve been Bournemouth beach or one of those Bedouin camps as seen in films. I wouldn’t really know. This was my first experience of a desert. It may have suited Lawrence of Arabia but I didn’t fall in love with it. . First parade was a kit check and inspection. I suspected those who flogged kit in France were due a nasty shock. I was wrong. Any missing items were replaced without questions and called Lost In Transit. I wistfully regretted not selling a shirt or two in France.

We crumpled the desert with our shiny boots for a couple of weeks. Depots are made for marching. We also spent some time in a classroom learning, amongst other things, Caracol procedure, complications needed when dealing with Egyptian nicks. From what I heard about Egyptian police, if you only received a beating you were lucky. Surprisingly, the placed lacked motorbikes.

The camp was mainly staffed by German POWs. They spoke funny English like, “Vat you vant, eh?” and some strutted around like they won the war. Perhaps they did. They weren’t in leg irons and were as free as the red kites that constantly soared overhead looking to snatch a meal. The Germans ran the cookhouse and covered most of the humdrum jobs. They were trusted not to poison us.

Mauritian soldiers guarded the Depot. Fierce-looking men with long knives who looked like dacoits. Egyptians wisely steered well clear of these warriors. At 6pm each day someone above closed the shutters and the sun vanished quickly, not to appear again till 6.30am next morning. I was surprised to learn that the Egyptians used pounds and also strange bronze coins called akkers with holes in the centre so the locals could string them together like beads. We weren’t paid in real money anyway. Our meagre pay abroad was in BAFVs (BRITISH ARMED FORCES VOUCHERS), which we called soap coupons.

As usual there were riots in Cairo and we were mostly confined to camp. A new multi-story building was going up near the camp. The wooden scaffolding didn’t look very safe. The workers, presumably prisoners, were nearly naked men and urged on by overseers carrying long whips that they seemed delighted to wield indiscriminately. The Cairo Redcaps patrolled in Jeeps carrying Browning machine guns. I never saw a machine gun in training.

One day everyone was ordered to line up on the sandy square. We didn’t know why at first. Soon we discovered it was time for us to be allocated our Middle East units. Again the choice was arbitrary. We waited patiently and eventually the reinforcements required for each unit was detailed off. Foreign places like Cairo, Alexandria, Benghazi, Tripoli, Palestine and the huge supply depot at Tel-el-Kebir were mentioned. Also about 20 men were picked to go to Greece. I was one of them. A disinterested lance corporal sitting behind a trestle table scribbled our names on a sheet of paper. All the training was wasted. I would have no dealings with Egyptian coppers.

I was beginning to realize that the place you were posted to depended where you stood on parade. You couldn’t make your own choice as there was no formality to selection. Just luck. My best friend at the time, Ron Hardman, went to Palestine. We’d been together since my first days at Mychett. A couple of years older than me with a wife and a couple of kids, he’d wangled his way out of the mines and army life suited him well. A happy soul, Jewish Irgun resistance killed him in Tel Aviv three months later.

The next journey was the return by train to Port Said and embarkation on the SS King David. This was a rusting tramp ship in which rows of bunks had been placed in the hold. Iron rings were set at intervals along the hull. Slaves carried on the ship long ago probably enjoyed travel as much as we did. It was huge, cold and damned uncomfortable during the several days voyage to Greece but nobody died. Strangely, I was never seasick again. We disembarked at the Athens port of Piraeus. That trip finally stewed my ambition to be a sailor.

From Piraeus we travelled by rail to Athens. It was a freight train with flat-bed bogies. Unbelievable. It’s a wonder no one fell off. At Athens station we were taken to 116 Provost Company by a Bedford 3 ton truck. On the way we went under a low bridge and unlucky L/Cpl Mellor, who was holding the canopy rail above his head had his hand crushed against the underside of the stone bridge. His career ended before it started. No one missed him.

At 116 Provost Company we were lined up and an officer detailed off ten men at the left end of the line. These ten were sent to Salonika. I was one of them. Again my onward journey depended on where I stood. I travelled to Salonika by troopship again. Travel overland was more dangerous than a night out in Ayia Napa. At Salonika I joined the 4th (British) Infantry Division Provost Company of over 100 men. At last, following eight wasted months I was about to become a Redcap.

The Company’s home was a commandeered sleazy hotel on the main street, Egnatia, in Salonika. It wasn’t the size of the London Hilton. A tramp’s heaven, there were no bathrooms or showers or even hot water, although armies of marauding bed bugs enjoyed the threadbare amenities. I never made friends with a single one. We fought them with powder and fire, more fierce than the Battle of the Bulge, and despite the massacres we still lost. Vouchers were supplied for the local public baths. An experience never to be missed. Blanco could not be got for love or gold. We used foot powder so wore equipment as gray as a pensioner’s head.

Again, the coin came down tails and I moved on. This time to Veroia, 50 miles north of Salonika, where I joined 28 Infantry Brigade Provost Section. The mountain town was sullen, misty and buried in snow. People actually lived there. Nervous townsfolk spent their time looking over their shoulders. It had taken eight month’s of pain and mind searching to reach there and I was a genuine Redcap at last. It may not be easier but the pretence was over. The real learning begins here. 10th Infantry Brigade section was stationed in Kavala. One day mounted Greek police there rode around with bandits’ heads speared on their lances. Nice people.

Corporal Turner was top banana in Veroia. He possessed the spark of a charged battery. Garrison Police from the infantry battalions made up half the section of 12. Like little children they weren’t allowed out on their own. Turner was a pleasant chap and caused no strife. He was without malice or pretence and lived like a monk. Too good to be true? Maybe. Or very shrewd. We followed him because he pulled the strings and we liked him. Wimps? Maybe.

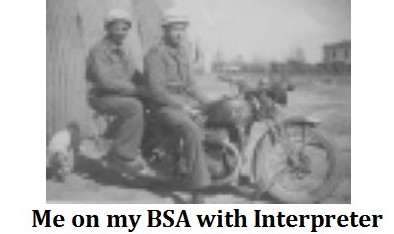

We were mobile with one Jeep and one BSA 500, which I grabbed. I soon began to drive as well. One icy morning Corporal Turner told me, “Take the Jeep and collect Harrison waiting at Brigade HQ.” I blinked and swallowed. “I can’t drive,” I whimpered. He shook his head with disapproval and clicked his tongue. He said in a tone that made me shrivel, “There’s the jeep. All it’s got is a steering wheel, an accelerator and gearstick. Simple. Just do it.” It was and I did. I thought back to those crossroads at Mychett and grinned.

Obnoxious Sergeant Curtis remained in Salonika so I was free of him for a few months, like getting rid of a bad smell. Years later I heard he went for a walk along the cliff-top at Freshwater in Dorset and didn’t stop when the cliff-top ended.

The 28 Brigade Commander was Brigadier Maxwell, who would be Provost Marshal later. It was mid winter and temperature in the mountains remained at below zero. The ground was covered in permanent snow. We had no cold weather clothing. The Nissen hut we occupied as usual boasted an iron stove but no fuel was available. We fired petrol in a can to try to keep warm.

Veroia was in the heart of bandit country. The Greeks were engaged in a wicked civil war and we needed to be very careful and alert when out and about. Greek army patrols were nervous and very trigger-happy. During every patrol I went on a chilly breeze caressed the nape of my neck and it wasn’t the winter weather. When challenged, which was often, we’d quickly call, “Anglika” and hold our breath. Some days rebel bodies were laid out near the town hall, displayed to warn rebel supporters.

We carried loaded pistols at all times. There were no orders about when to open fire. We decided. Sometimes on patrol I amused myself trying to shoot out streetlights but I was a lousy shot and never hit any. We kept that a secret from the bandits. Ammunition was freely available and not accounted for. Shooting was as common as chirping birds and nobody took any notice of a couple of pistol shots. The tired old town was sick of death and destruction.

If there were any civilian jalopies in the town they must be hibernating. The synagogue was older than the Acropolis but no Jews to attend it. The few greasy spoon tavernas gave us free food and drink or risked being placed Out of Bounds. Squeaky-clean cops are a myth. An occasional lonely scruffy bus with clattering snow chains belched smoke along the streets. It hadn’t been cleaned since Aristotle’s funeral. December arrived but no jingle bells. The people were so poor they couldn’t afford Christmas junk. Two infantry battalions were stationed there, The East Surreys and The Beds and Herts.

I think the Communists had day jobs. They only attacked at weekends. As soon as the first mortar shells whined overhead we scrambled under our beds like scuttling rats in a sewer. The ordnance landed with loud booming thuds like steam hammers. Very large steam hammers. No bomb shelters handy. Beds were as bomb proof as paper bags but felt safe.

Turner never turned a hair. He always stretched out on his charpoy reading, as cool as a fishmonger’s slab. I think he wore a mail vest and tin drawers. Despite the frights I was happy there and it’s a great feeling to be bombed and shot at and survive. It’s like trekking to the South Pole and returning triumphant with only a frostbitten fingernail.

When I returned to Salonika wiser and bomb happy I was attached to the SIB. That was the end of the beginning. A lot happened and centuries passed before I saw England again. Demob No.74 came slower than a sleeping tortoise. By then I decided King George deserved me.

There again, I’m the only one who really cared.

Les Hooper.

12th October 2013